I wrote the cover essay for Emigre 37, published this month.

Here’s the complete text:

Joint Venture: Writers, Designers, and the New Language of Collaboration

by Daniel X. O’Neil

This essay lays the rationale behind a new approach to the writer/designer relationship based on the ownership of intellectual property. This approach begins with a change in the way we describe dual artistic product and advocates a change in the structure of shared ownership and credit. It proposes a linguistic change to reflect a switch in emphasis from labor to ownership. It lifts the writer and designer, up until now cogs in the wheels of big publishing, out of the “work for hire” category (the ghetto of international intellectual property law) and into the center of a publishing operation, giving them artistic and financial control.

When collaborate was coined, it was the simple expression of co-labor. During World War II, however, the word was used to describe what the French did with the Germans when Hitler’s tanks rolled underneath the Arc de Triomphe. The word has since smacked of cooperation with the enemy. The image of collaboration is the picture of some grubby little clerk in the basement of the Pentagon making copies of civil defense documents to sell to Soviets. Certainly not a stable, honorable, enterprise is collaboration. Yet for years artists have presented the fruit of their labor underneath this stained banner. The focus of collaboration on “labor” is also a convenient way to deny artists ownership of their work and the right to exploit it. Factory workers are paid by the shift. The products of their work belong to the owner of the factory, who has all the rights to it. Collaboration is a fuzzy activity conducted on the fringes of society. There is a strong notion that artists ought to be happy to be invited to the collaboration for the love and joy of creation. Then they should go away. This wastes time and leads to marginalization and poverty for the collaborators. “Collaborate” also focuses on a tightly held, inward relationship with no regard for the rest of the world.

“Joint venture” is a forward-looking thing, facing outward to the rest of the world, a phrase of utility when engaging in commerce. It defines the relationship of joint venturers to each other, as well as to all other indi viduals and entities, by statute and case law. “Joint” as a word has a long history of being about property, about the holding together of things, and the action behind ownership. The other foot of joint is the venture, the stepping into the world and facing the possibilities and inevitabilities of life as a corporate structure. It in volves acting together and benefiting jointly from the expertise and interests of others, not dabbling in the other’s expertise and interests, because that is not an effective or profitable use of corporate resources. It is better to let each do their work. It also has the connotation of chance and danger, and what is more American than the confident roll of the dice? It takes guts to venture, and none to collaborate with an occupying army.

“Joint venture” provides the stable, legally recognized structure for the relationship among two or more people or entities engaged in interrelated industries joined for an express purpose. It is a 30-year old term rooted in American Business Language, which is the tongue of commerce all over the world. Instead of couching the fruit of dual product as the conspiratorial whispers of collaborators, joint venture is an up-front, widely accepted undertaking. The entity created when a writer and designer form a joint venture to create printed matter is called “publisher.” The startling realization is that all one needs to be a publisher is a writer, a designer, and a willingness to spend all your money on printing.

Onward and Forward to the Formulation of Joint Ventures!

* * *

Also in this edition, editor Rudy vander Lans interviewed me. Here’s that:

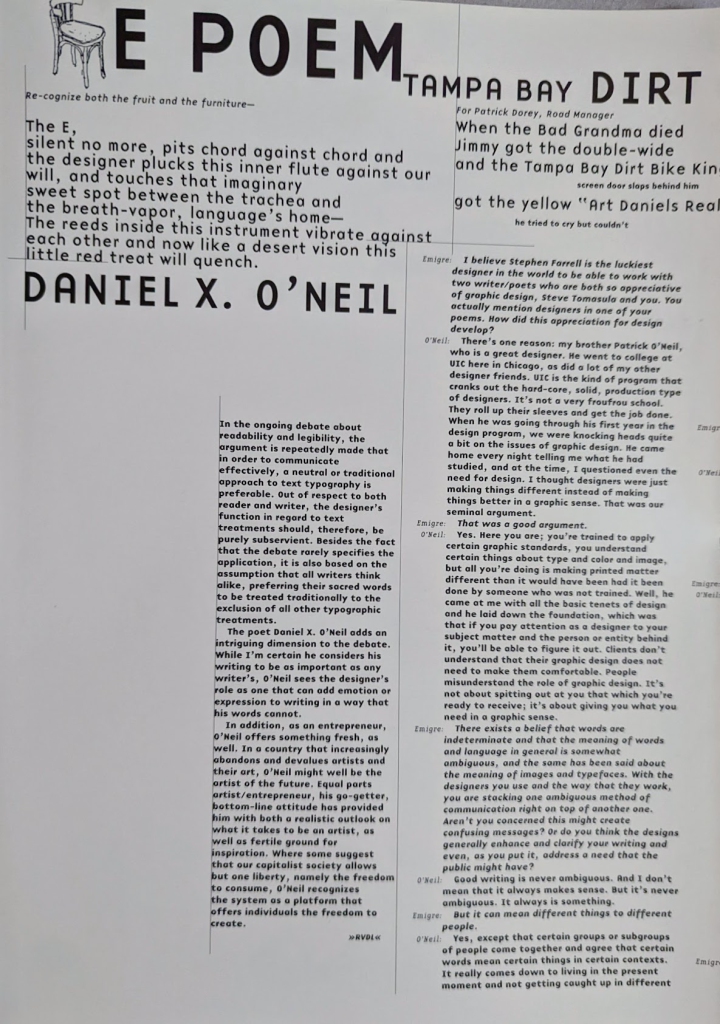

In the ongoing debate about readability and legibility, the argument is repeatedly made that in order to communicate effectively, a neutral or traditional approach to text typography is preferable. Out of respect to both reader and writer, the designer’s function in regard to text treatments should, therefore, be purely subservient. Besides the fact that the debate rarely specifies the application, it is also based on the assumption that all writers think alike, preferring their sacred words to be treated traditionally to the exclusion of all other typographic treatments.

The poet Daniel X. O’Neil adds an intriguing dimension to the debate. While I’m certain he considers his writing to be as important as any writer’s, O’Neil sees the designer’s role as one that can add emotion or expression to writing in a way that his words cannot.

In addition, as an entrepreneur, O’Neil offers something fresh, as well. In a country that increasingly abandons and devalues artists and their art, O’Neil might well be the artist of the future. Equal parts artist/entrepreneur, his go-getter, bottom-line attitude has provided him with both a realistic outlook on what it takes to be an artist, as well fertile ground for inspiration. Where some suggest that our capitalist society allows but one liberty, namely the freedom to consume, O’Neil recognizes the system as a platform that offers individuals the freedom to create.

RVDL«

Emigre: I believe Stephen Farrell is the luckiest designer in the world to be able to work with two writer/poets who are both so appreciative of graphic design, Steve Tomasula and you. You actually mention designers in one of your poems. How did this appreciation for design develop?

O’Neil: There’s one reason: my brother Patrick O’Neil, who is a great designer. He went to college at UIC here in Chicago, as did a lot of my other designer friends. UIC is the kind of program that cranks out the hard-core, solid, production type of designers. It’s not a very froufrou school. They roll up their sleeves and get the job done. When he was going through his first year in the design program, we were knocking heads quite a bit on the issues of graphic design. He came home every night telling me what he had studied, and at the time, I questioned even the need for design. I thought designers were just making things different instead of making things better in a graphic sense. That was our seminal argument.

Emigre: That was a good argument.

O’Neil: Yes. Here you are; you’re trained to apply certain graphic standards, you understand certain things about type and color and image, but all you’re doing is making printed matter different than it would have been had it been done by someone who was not trained. Well, he came at me with all the basic tenets of design and he laid down the foundation, which was that if you pay attention as a designer to your subject matter and the person or entity behind it, you’ll be able to figure it out. Clients don’t understand that their graphic design does not need to make them comfortable. People misunderstand the role of graphic design. It’s not about spitting out at you that which you’re ready to receive; it’s about giving you what you need in a graphic sense.

Emigre: There exists a belief that words are indeterminate and that the meaning of words and language in general is somewhat ambiguous, and the same has been said about the meaning of images and typefaces. With the designers you use and the way that they work, you are stacking one ambiguous method of communication right on top of another one. Aren’t you concerned this might create confusing messages? Or do you think the designs generally enhance and clarify your writing and even, as you put it, address a need that the public might have?

O’Neil: Good writing is never ambiguous. And I don’t mean that it always makes sense. But it’s never ambiguous. It always is something.

Emigre: But it can mean different things to different people.

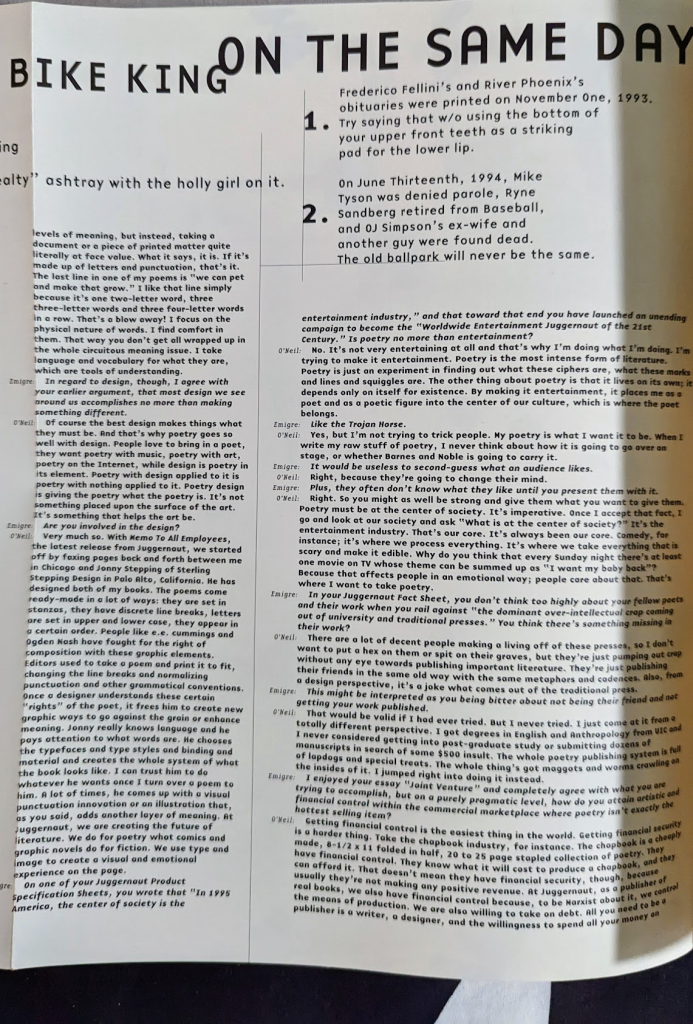

O’Neil: Yes, except that certain groups or subgroups of people come together and agree that certain words mean certain things in certain contexts. It really comes down to living in the present moment and not getting caught up in different levels of meaning, but instead, taking a document or a piece of printed matter quite literally at face value. What it says, it is. If it’s made up of letters and punctuation, that’s it. The last line in one of my poems is “we can pet and make that grow.. “I like that line simply because it’s one two-letter word, three three-letter words and three four-letter words in a row. That’s a blow away! I focus on the physical nature of words. I find comfort in them. That way you don’t get all wrapped up in the whole circuitous meaning issue. I take language and vocabulary for what they are, which are tools of understanding.

Emigre: In regard to design, though, I agree with your earlier argument, that most design we see around us accomplishes no more than making something different.

O’Neil: Of course the best design makes things what they must be. And that’s why poetry goes so well with design. People love to bring in a poet, they want poetry with music, poetry with art, poetry on the Internet, while design is poetry in its element. Poetry with design applied to it is poetry with nothing applied to it. Poetry design is giving the poetry what the poetry is. It’s not something placed upon the surface of the art. It’s something that helps the art be.

Emigre: Are you involved in the design?

O’Neil: Very much so. With Memo To All Employees, the latest release from Juggernaut, we started off by faxing pages back and forth between me in Chicago and Jonny Stepping of Sterling Stepping Design in Palo Alto, California. He has designed both of my books. The poems come ready-made in a lot of ways: they are set in stanzas, they have discrete line breaks, letters are set in upper and lower case, they appear in a certain order. People like e.e. cummings and Ogden Nash have fought for the right of composition with these graphic elements. Editors used to take a poem and print it to fit, changing the line breaks and normalizing punctuation and other grammatical conventions. Once a designer understands these certain “rights” of the poet, it frees him to create new graphic ways to go against the grain or enhance meaning. Jonny really knows language and he pays attention to what words are. He chooses the typefaces and type styles and binding and material and creates the whole system of what the book looks like. I can trust him to do whatever he wants once I turn over a poem to him. A lot of times, he comes up with a visual punctuation innovation or an illustration that, as you said, adds another layer of meaning. At Juggernaut, we are creating the future of literature. We do for poetry what comics and graphic novels do for fiction. We use type and image to create a visual and emotional experience on the page.

Emigre: On one of your Juggernaut Product Specification Sheets, you wrote that “In 1995 America, the center of society is the entertainment industry,” and that toward that end you have launched an unending campaign to become the “Worldwide Entertainment Juggernaut of the 21st Century.” Is poetry no more than entertainment?

O’Neil: No. It’s not very entertaining at all and that’s why I’m doing what I’m doing. I’m trying to make it entertainment. Poetry is the most intense form of literature. Poetry is just an experiment in finding out what these ciphers are, what these marks and lines and squiggles are. The other thing about poetry is that it lives on its own; it depends only on itself for existence. By making it entertainment, it places me as a poet and as a poetic figure into the center of our culture, which is where the poet belongs.

Emigre: Like the Trojan Horse.

O’Neil: Yes, but I’m not trying to trick people. My poetry is what I want it to be. When I write my raw stuff of poetry, I never think about how it is going to go over onstage, or whether Barnes and Noble is going to carry it.

Emigre: It would be useless to second-guess what an audience likes.

O’Neil: Right, because they’re going to change their mind.

Emigre: Plus, they often don’t know what they like until you present them with it.

O’Neil: Right. So you might as well be strong and give them what you want to give them. Poetry must be at the center of society. It’s imperative. Once I accept that fact, I go and look at our society and ask “What is at the center of society?” It’s the entertainment industry. That’s our core. It’s always been our core. Comedy, for instance; it’s where we process everything. It’s where we take everything that is scary and make it edible. Why do you think that every Sunday night there’s at least one movie on TV whose theme can be summed up as “I want my baby back”? Because that affects people in an emotional way; people care about that. That’s where I want to take poetry.

Emigre: In your Juggernaut Fact Sheet, you don’t think too highly about your fellow poets and their work when you rail against “the dominant over-intellectual crap coming out of university and traditional presses.” You think there’s something missing in their work?

O’Neil: There are a lot of decent people making a living off of these presses, so I don’t want to put a hex on them or spit on their graves, but they’re just pumping out crap without any eye towards publishing important literature. They’re just publishing their friends in the same old way with the same metaphors and cadences. Also, from a design perspective, it’s a joke what comes out of the traditional press.

Emigre: This might be interpreted as you being bitter about not being their friend and not getting your work published.

O’Neil: That would be valid if I had ever tried. But I never tried. I just come at it from an totally different perspective. I got degrees in English and Anthropology from UIC and I never considered getting into post-graduate study or submitting dozens of manuscripts in search of some $500 insult. The whole poetry publishing system is full of lapdogs and special treats. The whole thing’s got maggots and worms crawling on the insides of it. I jumped right into doing it instead.

Emigre: I enjoyed your essay “Joint Venture” and completely agree with what you are trying to accomplish, but on a purely pragmatic level, how do you attain artistic and financial control within the commercial marketplace where poetry isn’t exactly the hottest selling item?

O’Neil: Getting financial control is the easiest thing in the world. Getting financial security is a harder thing. Take the chapbook industry, for instance. The chapbook is a cheaply made, 8-1/2 x 11 folded in half, 20 to 25 page stapled collection of poetry. They have financial control. They know what it will cost to produce a chapbook, and they can afford it. That doesn’t mean they have financial security, though, because usually they’re not making any positive revenue. At Juggernaut, as a publisher of real books, we also have financial control because, to be Marxist about it, we control the means of production. We are also willing to take on debt. All you need to be a publisher is a writer, a designer, and the willingness to spend all your money on printing. The act of publishing is the act of printing. Sure, you have to market and promote and distribute and there’s a lot of activities that go along with being. a publisher, but the core activity of publishing is the act of printing. That’s what costs money. Now, to attain financial security, we have to go back to why poetry isn’t selling. Look at how many people walk in and out of bookstores in this country every single day and come out with stacks and stacks of these commercial products called “books.” People buy them by the tons. That tells me there’s a tremendous opportunity there. All we have to do is improve the quality of poetry and the poetry delivery system. If we do that, there’s tremendous opportunity for growth. The poetry delivery system is all screwed up because people are used to getting the stuff from these traditional presses and they’re turned off by it because it doesn’t affect them at all and it doesn’t speak to them at all. It has nothing to do with what goes on in their lives, has nothing to do with their fantasies and it doesn’t make them laugh or cry. That’s what we have to do: make it matter. If you make it matter, people will be receptive and sales will go up through the roof and as a publisher you’ll attain financial security. Forty years ago, nobody could have predicted that in the seventies and eighties, there were going to be five, six, seven comedy clubs in every city down to Broken Arrow, Oklahoma. It’s totally unprecedented. Nobody thought it could ever happen.

Emigre: You’re quite an optimist.

O’Neil: There’s no reason not to be.

Emigre: On the subject of intellectual property, I’d like to present you with a little scenario and get your reaction. Let’s say youbecome quite successful at what you’re doing with Juggernaut and you publish the work of another writer. You invest in publishing his or her book and perhaps invest in various promotions to announce the book to the public. At this time, you as a publisher are helping the career of this writer. Through the distribution system you have built, the contacts you have developed over time, and the money that you’ve earned, you now enable that other writer to benefit from your labor and investments. However, at this point you are pretty much in the red. You paid for the printing, editing, promotions, you paid for shipping the books to distributors, and you need to recoup that investment. Now, let’s say this book becomes quite a hit and the writer gets all sorts of invitations from other publishers and magazines. According to your manifesto, the writer should retain ownership over the work and therefore can take the some book that Juggernaut published, or any new work, to a major publisher and become a huge star. This was made possible to a large extent by your grass roots efforts. The point I’m making here is that the methods that large publishers use, the “work for hire” and “intellectual ownership” that you argue against in your abstract, might be the only method to get anything significant accomplished. It’s perhaps the only method by which you can truly develop and help an artist along.

O’Neil: When that happens, all I can say is “Pay me and leave.” That big publisher can’t reprint our book because we designed it, we made it look the Juggernaut way. They can take the writing and do it in their schlock way any day they want to.

Emigre: You’re putting a big chunk of faith in the design. That big publisher could say, “We’re not going to put any effort in the design; that costs too much money and it’s really quite unimportant. Let’s put it out very cheaply and print a million copies and, instead, we’ll invest the money in promoting the book and letting people know it exists and make it easily available.”

O’Neil: I’d say, “Give me my cut” and invite me to the signing party and I’d kiss the writer on the cheek. It’s a commercial world out there. If that writer feels somebody else can do a better job for him or her as a publisher, then indeed that person owns those words. I happen to have a contract. to a stake in it. A stake that is very well defined in a contract.

Emigre: Do you see Juggernaut as operating significantly differently from a large publishing house?

O’Neil: Yes. For one, large publishers endeavor keep the writers and designers as far away from each other as possible. They take the work and say, “Goodbye writer, see you later.” At Juggernaut, the writer and the designer communicate with each other until the work is sent to the printer.

Emigre: Since you have such high hopes for poetry to take up a more prominent place within society, wouldn’t you stand a much bigger chance to get your message out to the world with the help of a large, multi-national operation? Wouldn’t that also be a much bigger challenge? Although there’s a certain romanticism attached to the idea of working in the margins, it can also be explained as escapist. If you really want to change the world, or at least change the inner workings of large corporations in regard to publishing poetry, wouldn’t it be more effective to do that from the inside?

O’Neil: Sure. I’m not opposed to working for a major publisher. If a major publisher wants to have the same kind of relationship that major record companies have with independent labels, I’m for that. You want to infuse capital and let me do whatever I want, and whatever product deliver to you you market, that’s fine, let’s do it. Don’t get me wrong, I’m not Mr. Anti-Big Business. I want to be a big business. I want publishers to shake in their boots and run. 1 think I can do it better. I know I’m delivering poetry better than they are. And I’m delivering it to their clients like Barnes & Nobles, Tower, Borders. We have a system here and the system will work on any scale because we have always planned to be as big as possible. The poet is at the center, not to be relegated to the fringe of society.

Emigre: Being alternative never seems to jibe with making money, yet it’s obvious that the entire history of subcultures is a history of entrepreneurs.

O’Neil: I often get flack for promoting myself so aggressively. What’s so wrong with promoting yourself? America is about self-promotion. Is there something wrong with publishing a book yourself? Am I supposed to be sitting in a corner throwing up on myself? I’ve got some real live literary products and I want everyone to buy them.

Emigre: When you start making money and start promoting yourself, it’s often seen as selling out. I like what Neil Young said in regard to this. He said that to him, selling out meant making a real good record and then selling them all out.

O’Neil: Right. And my quote is, “I promise never to sell out. I promise to have enough product, in stock, for everyone.”

Emigre: obviously I enjoy discussing the commercial side of what people do. On the other hand, it’s striking how commerce is dominating everything around us. Look at the world of professional sports; strikes over contracts, hold-outs, skyrocketing salaries, franchises moving to cities with the deepest pockets. Read Option and Spin magazines and most always the conversation with musicians turns to record deals, lawsuits, selling out, etc. Is that a sad development?

O’Neil: People should be able to talk freely about it when it’s time to talk about it. But let’s talk about it with lawyers. Then there’s a time and place for it. In the entertainment, I don’t think we should talk too much about that. Let’s have a little bit of artifice. Let’s just go out and give them the show. You’ve got a contract on the books, it’s pending all the time. That’s what so cool about it. But I don’t think it’s sad because usually when there’s conflict, it means that the talent figure is asking for more pay. Everything in the entertainment industry is based on the talent, so the creative talent should get the most money. That makes people nervous.

Emigre: Has your current job as a paralegal contributed in any way to your Juggernaut venture other than providing you with a steady income?

O’Neil: Tremendously. I work in a litigation department at a major law firm. When a person or a company gets involved in full-blown litigation, each of the parties has to turn over all the accounting books and correspondence and internal memos and financial transactions and all the guts of their business to the other parties in the litigation. After analyzing, qualifying, quantifying, indexing, and organizing these types of documents, you get to know what it takes to run a business.. Working in a law firm has also given me access to nice people called lawyers who are willing to give me legal advice about my ventures.

Emigre: It’s interesting how that seeps back into your work. I just read your poem about the ASCAP man.

O’Neil: I was reading all these copyright cases and I was really into the minute distinctions upon which courts have decided who owned what and how much a particular original thought was worth. The name “ASCAP” kept popping up of course, and they never lose! They have guys

who run around and sit in bars and wait for the jukebox to go on and voila!

Judgment in favor of ASCAP.

Emigre: You recently sat in on a panel at the UNDERGROUND PRESS CONFERENCE in Chicago

at DePaul University. What were some of the discussions about?

It was all about the zine movement, which is a network of publishers,

reviewers and readers who buy and trade literature through the mail. I sat on

one panel about copyright versus anti-copyright. That was a lonely battle with those phreaks. My position was that the copyright law of the United States of America fosters the creation of new work. I’m completely in favor of copyright

protection. But I’m also completely in favor of sampling other people’s work

and then folding it into a larger work and not paying for it.

Emigre: Isn’t that contradictory? O’Neil: It’s fuzzy, but it’s not contradictory. We’ll just have to develop it by people

suing each other. That’s how the law moves forward. The whole thing is about how much you take from an original work and how much damage you cause to another person’s market.

What was the prevailing attitude towards copyright? An attitude of ill-informed naivete; all these people saying “Hey man, I’m

Emigre: O’Neil:

O’Neil:

doing it for the love of blah, blah, blah…” I say copyright is the mechanism by which underground people or independent people or people without the resources can create a stable entity. There’s only so much land in this world, but you can wake up every single day and create brand new intellectual property. That’s beautiful. So why would you want to be anti-copyright when it gives you the mechanism to do what you want to do? People think that it stifles creation, but the thing is, a copyright does not prohibit other people from copying your work. It prohibits them from doing so without your permission. Most people don’t see that distinction. These people would proudly proclaim their zine was an “anti-copyright publication.” They’d say “Just let us know if you reprint it.” The thing is, they’re operating one hundred percent in accordance with the guidelines of the copyright law. All they’re doing is setting forth the conditions under which someone can copy their work. That means they have control over their work and that they’re using the copyright laws to their advantage. People fight and fight for nothing. Smashing Pumpkins got it right in their new song Bullet with Butterfly Wings when they sang “despite all my rage/I am still just a rat in a cage.” No matter how alternative or anti-copyright you think you are, you’re still just a consumer of goods and services. My life is based on filling up my part of the cage with some of the best literary goods and services of the late 20th century, and they’re all for sale. There’s no reason why I shouldn’t be able to make a life out of that.

End